Last Letters from Menatone Mrs. C. H. Spurgeon THE love-letters of twenty blessed years have been reluctantly lifted from their hiding-place, and re-read with unspeakable love and sorrow. They are full of brightness, and the fragrance of a deep and abiding affection; and filled with every detail concerning my beloved and his doings which could be precious to the heart of a loving wife. But, alas! each year, some part of the holiday time at Mentone was overshadowed by what appeared to be an inevitable illness, when the dear preacher was laid aside, and days and nights of wearisome pain were appointed to him. He had always worked up to the latest moment, and to the utmost point of endurance, so it was not surprising that, when the tension was relaxed, nature revenged herself upon the weary body by setting every nerve on fire, and loading every vein with gout-poison, to act as fuel to the consuming flame. 'I feel as if I were emerging from a volcano,' he wrote, at the beginning of a convalescent period; but even at such a time his sense of humour asserted itself, for his pen had sketched the outlines of a conical hill, out of the crater of which his head and shoulders were slowly rising, while the still-imprisoned lower limbs set forth the sad truth that all was not yet well with them.

These chronicles would scarcely be complete without some further particulars concerning his life on the Riviera--how he enjoyed his pleasures, how he bore his pains, how he worked when God gave him relief from sickness, and how, always and ever, his loving heart was 'at home' with me. He kept up a daily correspondence with unflagging regularity; and when unable to use his pen, through severe suffering or weakness, the letter came as usual, either dictated by him, or altogether written by his devoted secretary.

I have selected, as the material for this chapter, the last letters which were written to me from Mentone, and which cover a period of nearly three months, for he left London on November 11, 1890, and returned February 5, 1891. Passing over the days of travel, which had no special interest, the arrival at Mentone is thus recorded on a post card:--'What heavenly sunshine! This is like another world. I cannot quite believe myself to be on the same planet. God grant that this may set me all right! Only three other visitors in the hotel--three American ladies--room for you. So far, we have had royal weather, all but the Tuesday. Now the sea shines like a mirror before us. The palms in front of the windows are as still as in the Jubilee above. The air is warm, soft, balmy. We are idle--writing, reading, dawdling. Mentone is the same as ever, but it has abolished its own time, and goes by Paris.

This bright opening of the holiday was quickly overclouded, for the next day came the sad news that gout had fastened upon the patient's right hand and arm, and caused him weary pain. Yet he wrote: 'The day is like one in Eden before our first parents fell. When my head is better, I shall enjoy it. I have eau de Cologne dripped on to my hot brain-box; and, as I have nothing to do but to look out on the perfect scene before me, my case is not a bad one.' But, alas! the 'case' proved to be very serious, and a painful time followed. These sudden attacks of the virulent enemy were greatly distressing and discouraging; one day, Mr. Spurgeon would be in apparent health and good spirits; and the next, his hand, or foot, or knee, would be swollen and inflamed, gout would have developed, and all the attendant evils of fever, unrest, sleeplessness, and acute suffering, would manifest themselves with more or less severity.

In the present instance, the battle raged for eight days with much fury, and then God gave victory to the anxious combatants, and partial deliverance to the prisoner. Daily letters, written by Mr. Harrald during this period, were very tender records of the sickroom experiences--every detail told, and every possible consolation offered--but it was a weary season of suspense for the loving heart a thousand miles distant, and the trial of absence was multiplied tenfold by the distress of anxiety.

In the first letter Mr. Harrald wrote, he said: 'The one continual cry from Mr. Spurgeon is, "I wish I were at home! I must get home!" Just to pacify him, I have promised to enquire about the through trains to London; but, of course, it would be impossible for him to travel in his present condition. Everyone is very kind, sympathetic, attentive, and ready to do anything that can be done to relieve or cheer the dear sufferer. I have just asked what message he wishes to send to you. He says, "Give her my love, and say I am very bad, and I wish I were at home for her to nurse me; but, as I am not, I shall be helped through somehow."'

Curiously enough, The Times of the following day had a paragraph to the effect that 'Mr. Spurgeon will stay at Mentone till February;' and when Mr. Harrald read this aloud, the dear patient remarked, 'I have not said so, but I am afraid I shall have to do it;' and the prophecy was fulfilled.

After eight days and nights of alternate progress and drawback, there came to me a half-sheet of, paper, covered with extraordinary hieroglyphic characters, at first sight almost unreadable. But love deciphered them, and this is what they said: 'Beloved, to lose right hand, is to be dumb. I am better, except at night. Could not love his darling more. Wished myself at home when pains came; but when worst, this soft, clear air helps me. It is as heaven's gate. All is well. Thus have I stammered a line or two. Not quite dumb, bless the Lord! What a good Lord He is! I shall yet praise Him. Sleeplessness cannot so embitter the night as to make me fear when He is near.' This pathetic little note is signed, 'Your own beloved Benjamite,' for it was the work of his left hand.

I think the effort was too much for him, for two more letters were written by Mr. Harrald; but a tender pleasantry, recorded in one of them, showed me that my beloved was on the road to recovery. 'Our dear Tirshatha,' Says Mr. Harrald, 'has been greatly pleased with your letter received to-day; your exhilaration appears to have favourably affected him. He says that he hopes the time will speedily arrive when he will be able to offer you his hand!'

After this, the daily correspondence from his own pen is resumed, and in the first letter he strikes his usual key-note of praise to God: 'Bless the Lord! I feel lighter and better; but oh, how weak! Happily, having nothing to do, it does not matter. I have nearly lost a whole month of life since I first broke down, but the Lord will restore this breach.'

The next day--date of letter, Dec. 1, 1890,--he writes to his 'poor lamb in the snow' to tell her that 'this poor sheep cannot get its forefoot right yet, but it is far better than it was'--followed by the quaint petition, 'May the Good Shepherd dig you out of the snow, and many may the mangolds and the swedes be which He shall lay in the fold for His half-frozen sheep!'

Our Arctic experiences in England were balanced by wintry weather on the Riviera. 'We have had two gloriously terrific storms,' he says; 'the sea wrought, and was tempestuous; it flew before the wind like glass dust, or powdered snow. The tempest howled, yelled, screamed, and shrieked. The heavens seemed on fire, and the skies reverberated like the boom of gigantic kettle-drums. Hail rattled down, and then rain poured. It was a time of clamours and confusions. I went to bed at ten, and left the storm to itself; and I woke at seven, much refreshed. I ought to be well, but I am not, and don't know why.

Dec. 3, 1890.--'We had two drives yesterday, and saw some of the mischief wrought by the storm. The woodman, Wind, took down his keenest axe, and went straight on his way, hewing out a clean path through the olives and the pines. Here he rent off an arm, there he cut off a head, and yonder he tore a trunk asunder, like some fierce Assyrian in the days ere pity was born. The poor cottagers were gathering the olives from the road, trying to clear off the broken boughs before they bore down other trees, and putting up fences which the storm had levelled with the ground. They looked so sad as they saw that we commiserated them. To-day, so fair, so calm, so bright, so warm, is as a leaf from the evergreen trees of Heaven. Oh, that you were here!'

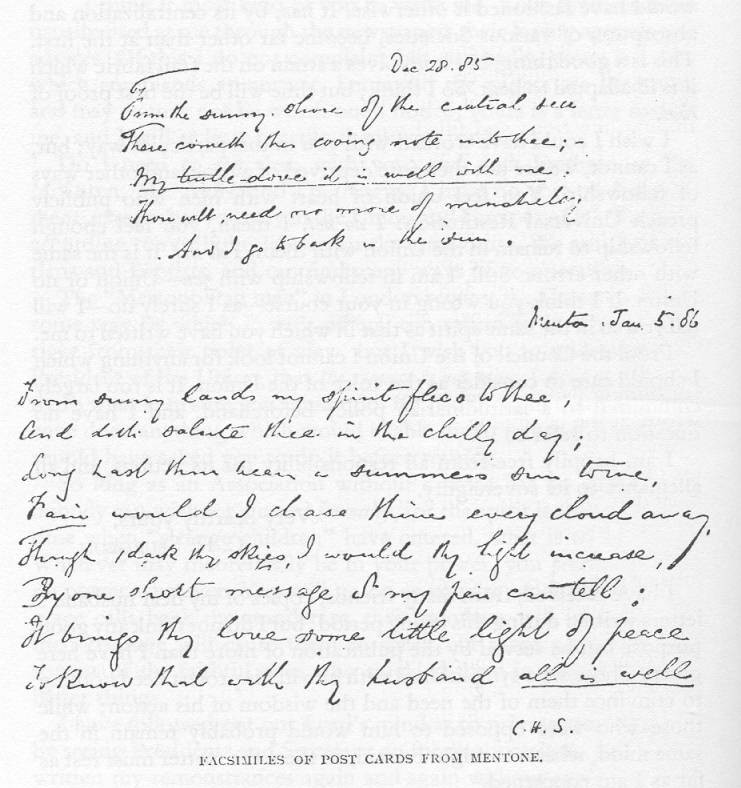

For the next four days, I received post cards only. There was a loving arrangement between us that these missives should be used when we were busy, or had not much to tell; but my beloved could always say a great many things on these little messengers. He knew how to condense and crystallize his thoughts, so that a few brief choice sentences conveyed volumes of tender meaning. I have commenced this chapter with facsimiles of two of his poetical post cards of earlier date; here are two specimens belonging to the period of which I am writing: