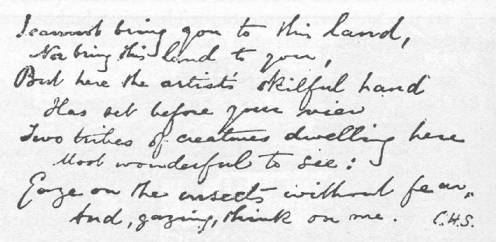

The Gorbio valley was one of the special haunts of the trap-door spiders until visitors so ruthlessly destroyed their wonderful under ground homes. Concerning these and other curious creatures, the Pastor wrote to Mrs. Spurgeon: 'How I wish you could be here to see the spiders' trap-doors! There are thousands of them here, and the harvesting ants also, though the wise men declared that Solomon was mistaken when he said, "They prepare their meat in the summer." I shall send you a book about them all.' When the volume arrived, it proved to be Harvesting Ants and Trap-door Spiders, by J. Traherne Moggridge. On its fly-leaf was the choice inscription:

One of the charms of Mentone to Spurgeon was that he could constantly see there illustrations of Biblical scenes and manners and customs. He frequently said he had no desire to visit Palestine in its forlorn condition, for he had before his eyes in the Riviera, an almost exact representation of the Holy Land as it was in the days of our Lord. He was greatly interested in an article written by Hugh Macmillan upon this subject, in which that devoted student of nature traced many minute resemblances between the climate, the conformation of the country, the fauna and flora, and the habits of the people in the South of France of today, and those of the East in the time when the Lord trod 'those holy fields.' In several of his Sabbath afternoon communion addresses, the Pastor alluded to the many things that continually reminded him of 'Immanuel's land,' while the olive trees were a never-failing source of interest and illustration. One of the works, with which he had made very considerable progress, was intended to be, if possible, an explanation of all the Scriptural references to the olive.

Spurgeon often remarked that there were many Biblical allusions which could not be understood apart from their Oriental associations; and, as an instance, he said that some people had failed altogether to catch the meaning of Isaiah 57:20, 'The wicked are like the troubled sea, when it cannot rest, whose waters cast up mire and dirt.' Those who have affirmed that the sea never can rest have not seen the Mediterranean in its most placid mood, when for days or even weeks at a time there is scarcely a ripple upon its surface. During that calm period, all sorts of refuse accumulate along the shore; and then, when the time of tempest comes, anyone who walks by the side of the agitated waters can see that they do 'cast up mire and dirt.' Usually, during the Pastor's stay at Mentone, there was at least one great storm, either far out at sea, or near at hand. In 1882, in one of his letters home, he wrote the following graphic description of the scene he had just witnessed:

'This afternoon, I have been out to watch the sea. There was a storm last night, and the sea cannot forgive the rude winds, so it is avenging its wrongs upon the shore. The sun shone at 3 o'clock, and there was no wind here; but away over the waters hung an awful cloud, and to our left a rainbow adorned another frowning mass of blackness. Though much mud was under foot, all the world turned out to watch the hungry billows rush upon the beach. In one place, they rolled against the esplanade, and then rose, like the waterworks at Versailles, high into the air, over the walk, and across the road, making people run and dodge, and leaving thousands of pebbles on the pavement. In, another place, the sea removed all the foreshore, undermined the walls, carried them away, and then assailed the broad path, which it destroyed in mouthfuls, much as a rustic eats bread-and-butter'! Here and there, it took away the curb; I saw some twelve feet of it go, and then it attacked the road. It was amusing to see the people move as a specially big wave dashed up. The lamp-posts were going when I came in, and an erection of solid stone, used as the site of a pump, was on the move. Numbers of people were around this as I came in at sundown; it was undermined, and a chasm was opening between it and the road. Men were getting up the gas pipes, or digging into the road to cut the gas off. I should not wonder if the road is partly gone by the morning. Though splashed with mud, I could not resist the delight of seeing the huge waves, and the sea birds flashing among them like soft lightnings. The deep sigh, the stern howl, the solemn hush, the booming roar, and the hollow mutter of the ocean were terrible and grand to me. Then the rosy haze of the far-ascending spray, and the imperial purple and azure of the more-distant part of the waters, together with the snow-white manes of certain breakers on a line of rock, made up a spectacle never to be forgotten. Far away, in the East, I saw just a few yards of rainbow standing on the sea. It seemed like a lighthouse glimmering there, or a ship in gala array, dressed out with the flags of all nations. O my God, how glorious art Thou! I love Thee the better for being so great, so terrible, so good, so true. "This God is our God, for ever and ever."'

Another phenomenon was thus described in a letter of the same period:

'About six in the evening, we were all called out into the road to see a superb Aurora Borealis--a sight that is very rarely seen here. Natives say that it is twelve years since the last appearance, and that it means a cold winter which will drive people to Mentone. Our mountains are to the North, and yet, above their tops, we saw the red glare of this wonderful visitant. "Castella is on fire," said an old lady, as if the conflagration of a million such hamlets could cause the faintest approximation to the Aurora, which looked like the first sight of a world on fire, or the blaze of the day of doom.'

Spurgeon had been at Mentone on so many occasions that he had watched its growth from little more than a village to a town of considerable size. He had so thoroughly explored it that he knew every nook and cranny, and there was not a walk or drive in the neighbourhood with which he was not perfectly familiar. His articles, in The Sword and the Trowel, on the journey from 'Westwood' to Mentone, and the drives around his winter resort, have been most useful to later travellers, and far more interesting than ordinary guide-books. Many of the villas and hotels were associated with visits to invalids or other friends, and some were the scenes of notable incidents which could not easily be forgotten.

At the Hôtel d'Italie, the Pastor called to see John Bright, who was just then in anything but a bright frame of mind. He was in a very uncomfortable room, and was full of complaints of the variations in temperature in the sunshine and in the shade. His visitor tried to give him a description of Mentone as he had known it for many years, but the great tribune of the people seemed only anxious to get away to more congenial quarters. The Earl of Shaftesbury was another of the notable Mentone visitors whom the Pastor tried to cheer when he was depressed about religious and social affairs in England and on the Continent.

The genial Sir Wilfrid Lawson, Member of Parliament and temperance advocate, scarcely needed anyone to raise his spirits, for he was in one of his merriest moods when he met Mr. Spurgeon at the hotel door, and the half-hour they spent together was indeed a lively time. The Right Hon. G. J. Shaw-Lefevre was another politician whom the Pastor met at Mentone. The subject of Home Rule for Ireland was just then coming to the front, and the Liberal statesman heard that day what Mr. Spurgeon thought of Mr. Gladstone's plans; the time came when the opinions then expressed privately were published widely throughout the United Kingdom, and materially contributed to the great leader's defeat in 1886.

In the earlier visits to Mentone, the Pastor stayed at the Hôtel des Anglais. In later years he used often to say that he never passed that spot without looking at a certain room, and thanking God for the merciful deliverance which he there experienced. One day he was lying in that room, very ill, but he had insisted upon the friends who were with him going out for a little exercise. Scarcely had they left, when a madman who had eluded the vigilance of his keepers rushed in, and said, ‘I want you to save my soul.' With great presence of mind, the dear sufferer bade the poor fellow kneel down by the side of the bed, and prayed for him as best he could under the circumstances. Spurgeon then told him to go away, and return in half an hour. Providentially, he obeyed. As soon as he was gone, the doctor and servants were summoned, but they were not able to overtake the madman before he had stabbed someone in the street. Only a very few days later, he met with a terribly tragic end.

In the garden of the same hotel, the Pastor once had an unusual and amusing experience. A poor organ-grinder was working away at his instrument; but, evidently, was evoking more sound than sympathy. Spurgeon, moved with pity at his want of success, took his place, and ground out the tunes while the man busily occupied himself in picking up the coins thrown by the numerous company that soon gathered at the windows and on the balconies to see and hear the English preacher play the organ! When he left off, other guests also had a turn at the machine; and, although they were not so successful as the first amateur player had been, when the organ man departed he carried away a heavier purse and a happier heart than he usually took home.

It was while staying at the Hôtel des Anglais that the Pastor adopted a very original method of vindicating one of the two Christian ordinances which were always very dear to him. At a social gathering, at which Spurgeon and a large number of friends were present, John Edward Jenkins, M.P., the author of Ginx's Baby, persistently ridiculed believers' baptism. It was a matter of surprise to many that he did not at once get the answer that he might have been sure he would receive sooner or later. The party broke up, however, without anything having been said by the Pastor upon the question, but it was arranged that, the next day, all of them should visit Ventimiglia, about six miles to the East. On reaching the cathedral, Spurgeon led the way to the baptistery in the crypt; and when all the company had gathered round the old man who was explaining the objects of interest, the Pastor said to his anti-immersionist friend, 'Mr. Jenkins, you understand Italian better than we do, will you kindly interpret for us what the guide is saying?' Thus fairly trapped, the assailant of the previous evening began, 'This is an ancient baptistery. He says that, in the early Christian Church, baptism was always administered by immersion.' The crypt at once rang with laughter, in which the interpreter joined as heartily as anyone, admitting that he had been as neatly 'sold' as a man well could be. He was not the only one who learnt that the combatant who crossed swords with our Mr. Great-heart might not find the conflict to his permanent advantage.

For several years, Mr. Spurgeon stayed at the Hôtel Beau Rivage. As he generally had several companions, or friends who wished to be near him, his party usually occupied a considerable portion of the small building, and the general arrangements were as homelike as possible, even to the ringing of a bell when it was time for family prayer. Not only were there guests in the house who desired to be present, but many came from other hotels and villas in the neighbourhood, and felt well rewarded by the brief exposition of the Scriptures and the prayer which followed it. Those of the company who were members of any Christian church asked permission to attend the Lord's-day afternoon communion service, and it frequently happened that the large sitting-room was quite full, and the folding doors had to be thrown back, so that some communicants might be in the room adjoining. On the Sabbath morning, the Pastor usually worshipped with the Presbyterian friends at the Villa les Grottes; occasionally giving an address before the observance of the Lord's supper, and sometimes taking the whole service. Although away for rest, an opportunity was generally made for him to preach, at least once during the season, at the French Protestant Church, when a very substantial sum was collected for the poor of Mentone. He also took part in the united prayer-meetings in the first week of the year, and sometimes spoke upon the topic selected for the occasion.

It is scarcely possible to tell how many people were blessed under the semi-private ministry which Spurgeon was able to exercise during his holiday. He used, at times, to feel that the burden became almost too great to be borne, for it seemed as if all who were suffering from depression of spirit, whether living in Mentone, Nice, Cannes, Bordighera, or San Remo, found him out, and sought the relief which his sympathetic heart was ever ready to bestow. In one case, a poor soul, greatly in need of comfort, was marvellously helped by a brief conversation with him. The Pastor himself thus related the story, when preaching in the Tabernacle, in June, 1883:

'Some years ago, I was away in the South of France; I had been very ill there, and was sitting in my room alone, for my friends had all gone down to the mid-day meal. All at once it struck me that I had something to do out of doors; I did not know what it was, but I walked out, and sat down on a seat. There came and sat next to me on the seat a poor, pale, emaciated woman in the last stage of consumption; and looking at me, she said, "O Mr. Spurgeon, I have read your sermons for years, and I have learned to trust the Saviour! I know I cannot live long, but I am very sad as I think of it, for I am so afraid to die." Then I knew why I had gone out there, and I began to try to cheer her. I found that it was very hard work. After a little conversation, I said to her, "Then you would like to go to heaven, but not to die? "Yes, just so," she answered. "Well, how do you wish to go there? Would you like to ascend in a chariot of fire?" That method had not occurred to her, but she answered, "Yes, oh, yes!" "Well," I said, "suppose there should be, just round this corner, horses all on fire, and a blazing chariot waiting there to take you up to heaven; do you feel ready to step into such a chariot? " She looked up at me, and she said, "No, I should be afraid to do that." "Ah!" I said, "and so should I; I should tremble a great deal more at getting into a chariot of fire than I should at dying. I am not fond of being behind fiery horses, I would rather be excused from taking such a ride as, that." Then I said to her, "Let me tell you what will probably happen to you; you will most likely go to bed some night, and you will wake up in heaven." That is just what did occur not long after; her husband wrote to tell me that, after our conversation, she had never had any more trouble about dying; she felt that it was the easiest way into heaven, after all, and far better than going there in a whirlwind with horses of fire and chariots of fire, and she gave herself up for her heavenly Father to take her home in His own way; and so she passed away, as I expected, in her sleep.'

The testimony of one American minister is probably typical of that of many others who came under Spurgeon's influence at Mentone, In one of his letters to The Chicago Standard, Rev. W. H. Geistweit wrote: 'It has been said that, to know a man, you must live with him. For two months, every morning, I found myself in Mr. Spurgeon's sitting-room, facing the sea, with the friends who had gathered there for the reading of the Word and prayer. To me, it is far sweeter to recall those little meetings than to think of him merely as the great preacher of the Tabernacle. Multitudes heard him there while but few had the peculiar privilege accorded to me. His solicitude for others constantly shone out, An incident in illustration of this fact will never be forgotten by me. He had been very ill for a week, during which time, although I went daily to his hotel, he did not leave his bed, and could not be seen. His suffering was excruciating. A little later, 'I was walking in the street, one morning, when he spied me from his carriage. He hailed me, and when I approached him, he held out his left hand, and said cheerily, "Oh, you are worth five shillings a pound more than when I saw you last!" And letting his voice fall to a tone of deep earnestness, he added, "Spend it all for the Lord."’

A gentleman, who was staying in the hotel at Mentone, where the Pastor spent the winter of 1883, wrote: 'As an instance of the rapidity of Mr. Spurgeon's preparation, the following incident may be given. There came to him, from London, a large parcel of Christmas and New Year's cards. These were shown to some of the residents at the hotel, and a lady of our party was requested to choose one from them. The card she selected was a Scriptural one; it was headed, "The New Year's Guest," and in harmony with the idea of hospitality, two texts were linked together: "I was a stranger, and ye took me in;" and "As many as received him, to them gave he power to become the sons of God, even to them that believe on his name." The card was taken away by, the lady; but, on the following Lord's-day, after lunch, Spurgeon requested that it might be lent to him for a short time. The same afternoon, a service was held in his private room, and he then gave a most beautiful and impressive address upon the texts on the card. The sermonettel was printed in The Metropolitan Tabernacle Pulpit shortly after that date, and has always seemed to me a wonderful illustration of Spurgeon's great power. Later in the day, he showed me the notes he had made in the half-hour which elapsed between the time the card came into his possession and the service at which the address was delivered; and these, written on a half-sheet of notepaper, consisted of the two main divisions, each one with several sub-divisions, exactly as they appear in the printed address.'

Occasionally, Spurgeon sent home the outline which he had used at the Sabbath afternoon communion, with some account of the service. The address upon the words, 'Thou hast visited me in the night,' which was published in December, 1886, under the title, 'Mysterious Visits', contained quite a number of autobiographical allusions, such as the following: 'I hope that you and I have had many visits from our Lord. Some of us have had them, especially in the night, when we have been compelled to count the sleepless hours. "Heaven's gate opens when this world's is shut." The night is still; everybody is away; work is done; care is forgotten; and then the Lord Himself draws near. Possibly there may be pain to be endured, the head may be aching, and the heart may be throbbing; but if Jesus comes to visit us, our bed of languishing becomes a throne of glory. Though it is true that "He giveth His beloved sleep," yet, at such times, He gives them something better than sleep, namely, His own presence, and the fulness of joy which comes with it. By night, upon our bed, we have seen the unseen. I tried sometimes not to sleep under an excess of joy, when the company of Christ has been sweetly mine.'

The closing paragraph is a good illustration of the way in which Spurgeon made use of the scenes around him to impress his message upon his hearers:

'Go forth, beloved, and talk with Jesus on the beach, for He oft resorted to the sea-shore. Commune with Him amid the olive groves so dear to Him in many a night of wrestling prayer. If ever there was a country in which men should see traces of Jesus, next to the Holy Land, this Riviera is the favoured spot. It is a land of vines, and figs, and olives, and palms; I have called it "Thy land, O Immanuel." While in this Mentone, I often fancy that I am looking out upon the Lake of Gennesaret, or walking at the foot of the Mount of Olives, or peering into the mysterious gloom of the Garden of Gethsemane. The narrow streets of the old town such as Jesus traversed, these villages are such as He inhabited. Have your hearts right with Him, and He will visit you often, until every day you shall walk with God, as Enoch did, and so turn weekdays into Sabbaths, meals into sacraments, homes into temples, and earth into heaven. So be it with us! Amen.'