In making a rather rough classification of Spurgeon's pure fun, manifested under various aspects throughout his long public career, first may be placed a few incidents associated with a matter which he always regarded as of great importance--punctuality. Everyone who was acquainted with him knows how scrupulously punctual he was at all services and meetings, and that; unless something very unusual had detained him, he was ready to commence either the worship or the business proceedings at the exact minute fixed. In the New Park Street days, he was unavoidably late on one occasion when he was to meet the deacons. One of them, the most pompous of the whole company, who was himself noted for his punctuality, pulled out his watch, and held it up reproachfully before the young minister. Looking at it in a critical fashion, Spurgeon said, 'Yes; it's a very good watch, I have no doubt, but it is rather old-fashioned, isn't it?'

He had often to suffer inconvenience and loss of time because those who had asked for interviews with him were not at the place arranged at the appointed hour. Frequently, after allowing a few minutes' grace, he would go away to attend to other service, leaving word that, as those he expected had not come according to the arrangement made, they must wait until he could find some other convenient opportunity of meeting them. This was to him a method of giving a lesson which many greatly needed. 'Punctuality is the politeness of kings'; yet some who are 'kings and priests unto God' are sadly deficient in that particular virtue. Sometimes, the Pastor would laughingly say that perhaps those who came so late were qualifying to act as lawyers, whose motto would be, ‘Procrastination is the hinge of business; punctuality is the thief of time.'

'General' Booth once sent an 'aide-de-camp' to Spurgeon to ask for an interview for himself. The hour for him to come was named but it was several minutes past the time when he arrived. Spurgeon, though sympathizing with the efforts of the Salvation Army, never approved of what he called their 'playing at soldiers,' so he said, in a tone of gentle irony, 'Oh, General! military men should be punctual!' It appeared that the object of 'General' Booth was to ascertain if the Tabernacle could be lent to the Army for some great gathering; but he would not ask for the loan of the building until the Pastor gave him some sign that, if he did make such a request, it would be granted. There the matter rested.

The Pastor once had occasion to see Gladstone, the Prime Minister, at Downing Street. Having asked for an interview of ten minutes, he arrived punctually, and, having transacted the business about which he had called, rose to leave directly the allotted time had expired. 'The grand old man' was not willing to allow his visitor to go away so quickly--though he said he wished others who called upon him would be as prompt both in arriving and departing—and 'the two prime ministers,' as they were often designated, continued chatting for a good while longer. It was during the conversation which ensued that Spurgeon suggested to the great Liberal leader a grander measure of reform than any he had ever introduced. His proposal was, that all the servants of the State, whether in the Church, the Army, the Navy, or the Civil Service, should be excluded from Parliament, just as the servants in a private family are not allowed to make the rules and regulations under which the household is governed. Possibly, archbishops, bishops, generals, admirals, noble lords, and right honourable gentlemen might imagine that this suggestion was a sample of Mr. Spurgeon's pure fun, but he introduced it to Mr. Gladstone with the utmost seriousness, and he referred to it as a plan which would greatly and permanently benefit the whole nation, and which he believed his fellow-countrymen would adopt if it were laid before them by the great statesman to whom he submitted it.

* During a General Election, it was discovered, one Monday morning, that the front gates and walls of 'Helensburgh House' had been, in the course of the night, very plentifully daubed over with paint to correspond with the colours of the Conservative candidates for that division of Surrey. In speaking, at the Tabernacle, the same evening, concerning the disfigurement of, his premises, Spurgeon said, 'It is notorious that I am no Tory, so I shall not trouble to remove the paint; perhaps those who put it on will take it off when it has been there long enough to please them'; and, in due time, they did so.

The mention of a General Election recalls a characteristic anecdote which Spurgeon delighted to tell. He had gone to preach for his friend, John Offord, and quite unavoidably was a little late in arriving. He explained that there had been a block on the road, which had delayed him; and, in addition, he had stopped on the way to vote. 'To vote!' exclaimed the good man; 'but my dear brother, I thought you were a citizen of the New Jerusalem!' 'So I am,' replied Spurgeon, 'but my "old man" is a citizen of this world.' 'Ah! but you should mortify your "old man," ''That is exactly what I did; for my "old man" is a Tory, and I made him vote for the Liberals!'

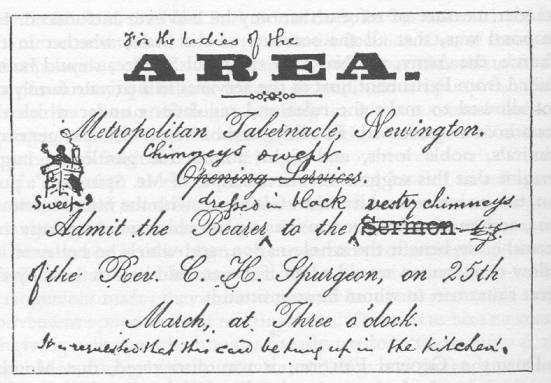

When the Tabernacle was about to be opened, tickets of admission to the various gatherings were printed. The one intended as a pass to the first service seemed to Mr. Spurgeon so unsuitable to the occasion that he turned it into a sweep's advertisement by annotating the front of it in this humorous style:

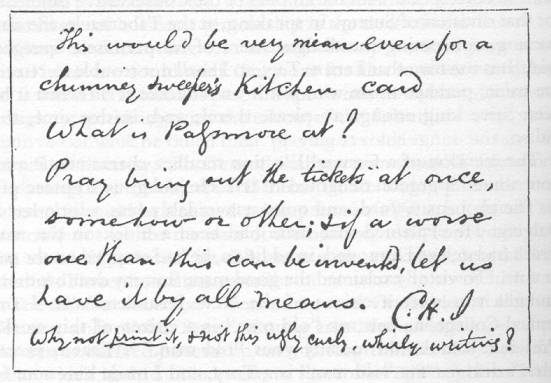

He also wrote on the back the comments and queries here reproduced in facsimile--

and sent the card to Mr. Passmore. One matter that always afforded Spurgeon the opportunity poking a little good-natured fun at his esteemed publishers (Messr. Passmore and Alabaster) was the non-arrival of proofs for which was looking. Frequently, at Mentone, or at some other place where the author was combining rest and work, Mr. Passmore or Mr. Alabaster would be asked about the 'Cock Robin shop' that he had left for a while. (A 'Cock Robin- shop' is the trade designation of a small printing-office where cheap booklets, such as The Death of Cock Robin, are issued.) It was a theme for perennial merriment, and no protestations of the publishers availed to put an end to it. If sermon or magazine proofs were delayed, the invariable explanation was, 'Perhaps they have had another order for Cock Robins, so my work has had to wait.'

On one occasion, Spurgeon and his secretary had gone to Bournemouth for a week; and, not knowing beforehand where they would be staying, the printers were instructed to send proofs to the Post Office, to be left till called for. On enquiry, the officials declared that they had nothing for Spurgeon, so the following telegram was despatched to London:--'When you have finished Cock Robins, please forward proofs of sermon and magazine.' It turned out that the fault was with the postal authorities, for they had only looked for letters, whereas the printed matter was in the office all the while in the compartment allotted to bookpost packets.

At one of the meetings when contributions for the new Tabernacle were brought in, the names of Knight and Duke were read out from the list of subscribers, whereupon Spurgeon said, 'Really, we are in grand company with a knight and a duke!’ Presently, 'Mr. King, five shillings,' was reported, when the Pastor exclaimed, 'Why, the king has actually given his crown! What a liberal monarch!' Directly afterwards, it was announced that Mr. Pig had contributed a guinea. 'That,' said Mr. Spurgeon, 'is a guinea-pig.'

The propensity of punning upon people's names was often indulged by the Pastor. Spurgeon could remember, in a very remarkable fashion, the faces and names of those whom he had once met; and if he made any mistake in addressing them, he would speedily and felicitously rectify it. A gentlemen, who had been at one of the annual College suppers, was again present the following year. The President saluted him with the hearty greeting, 'Glad to see you, Mr. Partridge.' The visitor was surprised to find himself recognized, but he replied, ‘My name is Patridge’ sir, not Partidge.' 'Ah, yes!’ was the instant rejoinder, 'I won't make game of you any more.'

A lady in Worcestershire, writing to Mrs. Spurgeon concerning a service at Dunnington, near Evesham, says:--'Mr. Spurgeon shook hands with seventy members of one family, named Bomford, who had gone to hear him. One of our deacons, a Mr. Alway, was at the same time introduced to him; and, in his own inimitable and ready way, he exclaimed, "Rejoice in the Lord, Alway!"'

Dr. John Campbell was once in a second-hand bookseller's shop with Spurgeon, and, pointing to Thorn on Infant Baptism, he said, 'There is "a thorn in the flesh" for you.' Mr. Spurgeon at once replied, 'Finish the quotation, my brother--"the messenger of Satan to buffet me."'

During the Baptismal Regeneration Controversy, a friend said to Spurgeon, 'I hear that you are in hot water.' 'Oh, dear no!' he replied; 'it is the other fellows who are in the hot water; I am the stoker, the man who makes the water boil!'

* Spurgeon made a very sparing use of his wit in the pulpit, though all his wits were always utilized there to the utmost. So one who objected to some humorous expression to which he had given utterance while preaching, he replied, 'If you had known how many others I kept back, you would not have found fault with that one, but you would have commended me for the restraint I had exercised.' He often said that he never went out of his way to make a joke--or to avoid one; and only the last great day will reveal how many were first attracted by some playful reference or amusing anecdote, which was like the bait to the fish, and concealed the hook on which they were soon happily caught.

At the last service in New Park Street Chapel, the Pastor reminded his hearers that the new Tabernacle, which they were about to enter, was close to 'The Elephant and Castle,' and then, urging them all to take their own share of the enlarged responsibilities resting upon them as a church and people, he said, 'Let every elephant bear his castle when we get there.' This was simply translating, into the dialect of Newington, Paul's words, 'Every man shall bear his own burden,' and, doubtless, the form of the injunction helped to impress it upon the memory of all who heard it.

No student of the Pastors' College, who listened to the notable sermon delivered in the desk-room by the beloved President, would be likely ever to forget the text of the discourse after it had been thus emphasized:--'Brethren, take care that this is always one of the Newington Butts--"But we preach Christ crucified." Let others hold up Jesus simply as an example, if they will; "but we preach Christ crucified." Let any, who like to do so, proclaim "another gospel, which is not another"; "but we preach Christ crucified."'

On one occasion, when Mr. Spurgeon was to preach in a Non-conformist ‘church' where the service was of a very elaborate character, someone else had been asked to conduct 'the preliminaries.' The preacher remained in the vestry until the voluntary, the lessons, the prayers, and the anthem were finished, then entering the pulpit, he said, 'Now, brethren, let us pray'; and the tone in which the last word was uttered indicated plainly enough what he thought of all that had gone before.

When William Cuff was minister at Providence Chapel, Hackney, one of the College Conference meetings was held there. The President presided, and in the course of his speech, he pointed to the organ, and said, ‘I look upon that as an innovation; and if I were here, I should want it to be an outovation, and then we would have an ovation over its departure. I was once asked to open an organ--I suppose the people wanted me to preach in connection with the introduction of the new instrument. I said that I was quite willing to open it as Simple Simon opened his mother's bellows, to see where the wind came from, but I could not take any other part in the ceremony.

Preaching at a chapel in the country, Mr. Spurgeon gave out Isaac Watts' version of the 91st Psalm--