Love, Courtship, and Marriage By MRS. C. H. SPURGEON WHEN I came to deal with the sacred and delicate task of writing this chapter, to record the events of the years 1854 and 1855, two courses only seemed to open before me--the one, to conceal, as gracefully as possible, under conventional phraseology and common-place details, the tender truth and sweetness of our mutual love-story--the other, to write out of the fullness of my very soul, and suffer my pen to describe the fair visions of the past as, one by one, they grew again before my eyes into living and loving realities. I chose the latter alternative, I felt compelled to do so. My hand has but obeyed the dictates of my heart, and, I trust also, the guidance of the unerring Spirit.

It may be an unusual thing thus to reveal the dearest secrets of one's past life, but I think, in this case, I am justified in the course I have taken. My husband once said, "You may write my life across the sky, I have nothing to conceal;" and I cannot withhold the precious testimony which these hitherto sealed pages of his history bear to his singularly holy and blameless character.

So, I have unlocked my heart, and poured out its choicest memories. Some people may blame my prodigality, but I am convinced that the majority of readers will gather up, with reverent hands, the treasures I have thus scattered, and find themselves greatly enriched by their possession.

It has cost me sighs, and multiplied sorrows, as I have mourned over my vanished joys; but, on the other hand, it has drawn me very near to "the God of all consolation", and taught me to bless Him again and again for having ever given me the priceless privilege of such a husband’s love.

Many years ago, I read a most pathetic story, which is constantly called to mind as the duties of this compilation compel me to read the records of past years, and re-peruse the long-closed letters of my beloved, and live over again the happy days when we were all-in-all to each other. I do not remember all the details of the incident which so impressed me, but the chief facts were these. A married couple were crossing one of the great glaciers of Alpine regions, when a fatal accident occurred. The husband fell down one of the huge crevasses which abound on all glaciers--the rope broke, and the depth of the chasm was so great that no help could be rendered, nor could the body be recovered. Over the wife's anguish at her loss, we must draw the veil of silence.

Forty years afterwards saw her, with the guide who had accompanied them at the time of the accident, staying at the nearest hotel to the foot of the glacier, waiting for the sea of ice to give up its dead; for, by the well-known law of glacier-progression, the form of her long-lost husband might be expected to appear, expelled from the mouth of the torrent, about that date. Patiently, and with unfailing constancy, they watched and waited, and their hopes were at last rewarded. One day, the body was released from its prison in the ice, and the wife looked again on the features of him who had been so long parted from her!

But the pathos of the story lay in the fact that she was then an old woman, while the newly-rescued body was that of quite a young and robust man, so faithfully had the crystal casket preserved the jewel which it held so long. The forty years had left no wrinkles on that marble brow, Time's withering fingers could not touch him in that tomb, and so, for a few brief moments, the aged lady saw the husband of her youth, as he was in the days which were gone for ever!

Somewhat similar has been my experience while preparing these chapters. I have stood, as it were, at the foot of the great glacier of Time, and looked with unspeakable tenderness on my beloved as I knew him in the days of his strength, when the dew of his youth was upon him, and the Lord had made him a mighty man among men. True, the cases are not altogether parallel, for I had my beloved with me all the forty years, and we grew old together; but his seven years in glory seem like half a century to me; and now, with the burden of declining years upon me, I am watching and waiting to see my loved one again--not as he was forty years or even seven years ago, but he will be when I am called to rejoin him through the avenue of the grave, or at the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ with all His saints. So I am waiting, and "looking for that blessed hope, and the glorious reappearing of the great God and our Saviour Jesus Christ."

The first time I saw my future husband, he occupied the pulpit of New Park Street Chapel on the memorable Sunday when he preached his first sermons there. I was no stranger to the place. Many a discourse had I there listened to from Pastor James Smith (afterwards of Cheltenham)--a quaint and rugged preacher, but one well versed in the blessed art of bringing souls to Christ. Often had I seen him administer the ordinance of baptism to the candidates, wondering with a tearful longing whether I should ever be able thus to confess my faith in the Lord Jesus.

I can recall the old-fashioned, dapper figure of the senior deacon, of whom I stood very much in awe. He was a lawyer, and wore the silk stockings and knee-breeches dear to a former generation. When the time came to give out the hymns, he mounted an open desk immediately beneath the pulpit, and from where I sat, I had a side view of him. To the best of my remembrance, he was a short, stout man, and his rotund body, perched on his undraped legs, and clothed in a long-tailed coat, gave him an unmistakable resemblance to a gigantic robin; and when he chirped out the verses of the hymn in a piping, twittering voice, I thought the likeness was complete!

Well also did I know the curious pulpit without any stairs; it looked like a magnified swallow's-nest, and was entered from behind through a door in the wall. My childish imagination was always excited by the silent and "creepy" manner in which the minister made his appearance therein. One moment the big box would be empty--the next, if I had but glanced down at Bible or hymn-book, and raised my eyes again--there was the preacher, comfortably seated, or standing ready to commence the service! I found it very interesting, and though I knew there was a matter-of-fact door, through which the good man stepped into his rostrum, this knowledge was not allowed to interfere with, or even explain, the fanciful notions I loved to indulge in concerning that mysterious entrance and exit. It was certainly somewhat singular that, in the very pulpit which had exercised such a charm over me, I should have my first glimpse of the one who was to be the love of my heart, and the light of my earthly life. After Mr. Smith left, there came, with the passing years, a sad time of barrenness and desolation upon the church at New Park Street; the cause languished, and almost died, and none even dreamed of the overwhelming blessing which the Lord had in store for the remnant of faithful people worshipping there.

From my childhood, I had been a greatly-privileged favourite with Mr.and Mrs. Olney, Senr. ("Father Olney" and his wife), and I was a constant visitor at their homes, both in the Borough and West Croydon, and it was by reason of this mutual love that I found myself in their pew at the dear old chapel on that Sabbath evening, December 18th, 1853. There had been much excitement and anxiety concerning the invitation to the country lad from Waterbeach to come and preach in the honoured, but almost empty sanctuary; it was a risky experiment, so some thought, but I believe that, from the very first sermon he heard him preach, dear old "Father Olney's" heart was fixed in its faith that God was going to do great things by this young David.

When the family returned from the morning service, varied emotions filled their souls. They had never before heard just such preaching; they were bewildered, and amazed, but they had been fed with royal dainties. They were, however, in much concern for the young preacher himself, who was greatly discouraged by the sight of so many empty pews, and manifestly wished himself back again with his loving people, in his crowded chapel in Cambridgeshire. "What can be done?" good Deacon Olney said; "we must get him a better congregation to-night, or we shall lose him!" So, all that Sabbath afternoon, there ensued a determined looking-up of friends and acquaintances, who, by some means or other, were coaxed into giving a promise that they would be at Park Street in the evening to hear the wonderful boy preacher. "And little Susie must come, too," dear old Mrs. Olney pleaded. I do not think that "little Susie" particularly cared about being present; her ideas of the dignity and propriety of the ministry were rather shocked and upset by the reports which the morning worshippers had brought back concerning the young man's unconventional outward appearance! However, to please my dear friends, I went with them, and thus was present at the second sermon which my precious husband preached in London.

Ah! how little I then thought that my eyes looked on him who was to be my life's beloved; how little I dreamed of the honour God was preparing for me in the near future! It is a mercy that our lives are not left for us to plan, but that our Father chooses for us; else might we sometimes turn away from our best blessings, and put from us the choicest and loveliest gifts of His providence. For, if the whole truth be told, I was not at all fascinated by the young orator's eloquence, --while his countrified manner and speech excited more regret than reverence. Alas, for my vain and foolish heart! I was not spiritually-minded enough to understand his earnest presentation of the gospel, and his powerful pleading with sinners, but the huge black satin stock, the long, badly-trimmed hair, and the blue pocket-handkerchief with white spots, which he himself has so graphically described--these attracted most of my attention, and, I fear, awakened some feelings of amusement. There was only one sentence of the whole sermon which I carried away with me, and that solely on account of its quaintness, for it seemed to me an extraordinary thing for the preacher to speak of the "living stones in the Heavenly Temple perfectly joined together with the vermilion cement of Christ's blood."

I do not recollect my first introduction to him; it is probable that he spoke to me, as to many others, on that same Sabbath evening, but when the final arrangement was made for him to occupy New Park Street pulpit, with a view to the permanent pastorate, I used to meet him occasionally at the house of our mutual friends, Mr. and Mrs. Olney, and I sometimes went to hear him preach.

I had not at that time made any open profession of religion, though I was brought to see my need of a Saviour under the ministry of the Rev. S. B. Bergne, of the Poultry Chapel, about a year before Mr. Spurgeon came to London. He preached, one Sunday evening, from the text, "The word is nigh thee, even in thy mouth, and in thy heart" (Romans x. 8), and from that service I date the dawning of the true light in my soul. The Lord said to me, through His servant, "Give Me thine heart," and, constrained by His love, that night witnessed my solemn resolution of entire surrender to Himself. But I had since become cold and indifferent to the things of God; seasons of darkness, despondency, and doubt, had passed over me, but I had kept all my religious experiences carefully concealed in my own breast, and perhaps this guilty hesitancy and reserve had much to do with the sickly and sleepy condition of my soul when I was first brought under the ministry of my beloved. None could have more needed the quickening and awakening which I received from the earnest pleadings and warnings of that voice--soon to be the sweetest in all the world to me.

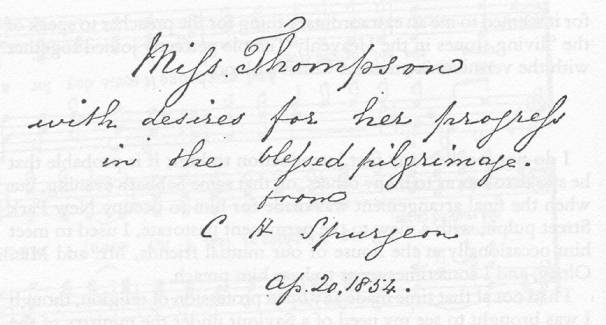

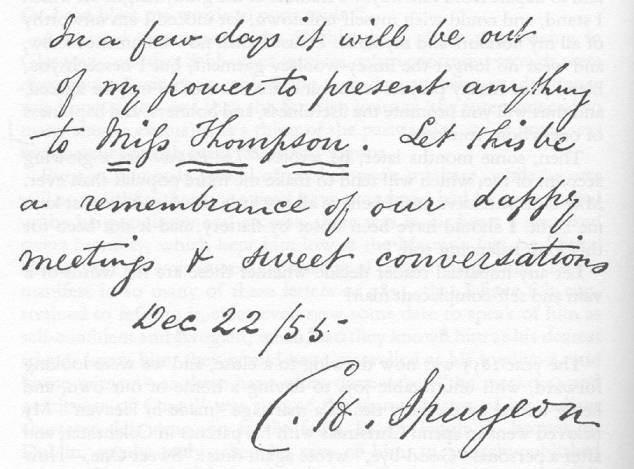

Gradually I became alarmed at my backsliding state, and then, by great effort, I sought spiritual help and guidance from William Olney ("Father Olney's" second son, and my cousin by marriage), who was an active worker in the Sunday-school at New Park Street, and a true Mr. Greatheart, and comforter of young pilgrims. He may have told the new Pastor about me--I cannot say; but, one day, I was greatly surprised to receive from Mr. Spurgeon an illustrated copy of The Pilgrim's Progress, in which he had written the inscription which is [here] reproduced . . . .

I do not think my beloved had, at that time, any other thought concerning me than to help a struggling soul Heavenward, but I was greatly impressed by his concern for me, and the book became very precious as well as helpful. By degrees, though with much trembling, I told him of my state before God; and he gently led me, by his preaching, and by his conversations, through the power of the Holy Spirit, to the cross of Christ for the peace and pardon my weary soul was longing for.

Thus things went quietly on for a little while; our friendship steadily grew, and I was happier than I had been since the days at the Poultry Chapel, but no bright dream of the future flashed distinctly before my eyes till the day of the opening of the Crystal Palace at Sydenham, on June 10, 1854. A large party of our friends, including Mr. Spurgeon, were present at the inauguration, and we occupied some raised seats at the end of the Palace where the great clock is now fixed. As we sat there talking, laughing, and amusing ourselves as best we could, while waiting for the procession to pass by, Mr. Spurgeon handed me a book, into which he had been occasionally dipping, and, pointing to some particular lines, said, "What do you think of the poet's suggestion in those verses!" The volume was Martin Tupper's Proverbial Philosophy, then recently published, and already beginning to feel the stir of the breezes of adverse criticism, which afterwards gathered into a howling tempest of disparagement and scathing sarcasm. No thought had I for authors and their woes at that moment. The pointing finger guided my eyes to the chapter on "Marriage", of which the opening sentences ran thus--